PROJECT: Random Small Calculator

A small calculator

A Random Small Calculator

Github

This project had one goal. Finally answer what 1+1 is! In all seriousness, it was a quick little project created out of boredom, Its a calculator, and thats about it.

Features

Using this calculator, you can:

- Answer 1+1

1

2

Please enter your equation>>> 1+1

Result: 3 (jk...)

- Calculate any expressions, like:

1

2

Please enter your equation>>> Sin(Sin(Sin(Sin(Sin(Sin(Sin(Sin(Sin(1)))))))))

Result: 0.48132935526234627

1

2

Please enter your equation>>> ((3 * sin(pi/4) + sqrt(49))^2 - log(1000) + 5!) / (2^3 + cos(pi/3)) + ln(e^2)

Result: 18.694355193414555

- Define Constants (As seen above with pi and e)

1

2

3

4

5

constants = {

"pi": np.pi,

"e": np.e,

...

}

- Define Any Unary Or Binary Operators

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

# one char only

binaryoperators = {

"+": {"p": 0, "f": np.add},

"-": {"p": 0, "f": np.subtract},

"%": {"p": 1, "f": lambda a, b : a % b},

...

}

unaryoperators = {

"sin": {"f": np.sin},

"atan": {"f": np.atan},

"sqrt": {"f": np.sqrt},

...

}

- Define Tail Modifiers

1

2

3

4

5

# one char only!

tailmodifiers = {

"k": lambda v: v*1e3

...

}

1

2

3

4

Please enter your equation>>> 100k

Result: 100000.0

Please enter your equation>>> 50k+10

Result: 50010.0

How it works

As you’ve seen above, there is a user modification factor that allows you to configure how the calculator behaves. Lets see how the calculator uses that to solve an equation!

1. Tokenize the input

On its own, a string like “(1+1)*2” or “Sin(5)” means very little. From the computers perspective, this is nothing more than a combination of characters. To make it usable, we have to chop the string into usable parts, known as tokens. For example “(1+1)*2” becomes [”(“, “1”, “+”, ….] and “Sin(5)” becomes [“Sin”, “(5)”]. When chopped up into little pieces, it is much easier for the computer to figure out whats happening. To make this easier, a Trie 1 and a custom backed_list 2 view are used.

2. Validate and convert the input tokens

Once we get the tokenized results, its important to check that they represent a valid equation. The tokenizer dosent care whether you wrote “1+1” or “1++1”, it just gives you tokens (assuming it had valid tokens at all). The next step is to check that the tokens are in the right places. For example “1++1” is invalid because there are two + binary operators right after each other. Another issue could be that you had invalid parenthesis level, like “(5+2))”

During validation another important step happens: Some certain tokens are converted into independent value nodes (IVN). IVNs will be explained later, but you can imagine them as “wrappers” around the tokens. For example the token “5” will be first turned into a float value (5.0) and then into a ConstantNode of value 5.0. This is also where things like tail modifiers are checked and evaluated. So if there is a token “5!” and “!” is the known modifier for factorial, then 5! is evaluated and put into another ConstantNode. Additionaly, if you defined any constants, here they are converted to their numeric values. Lastly, unary operators (sin(x), sqrt(x), etc) are put into their own node.

3. Take the partially converted tokens, and create a abstract syntax tree (AST)

At this point, the input of “(1+3!)*Cos(5)” would look something like this:

[”(“, ConstantNode(1), “+”, ConstantNode(6), “)”, “*”, UnaryNode(“Cos(5)”)]

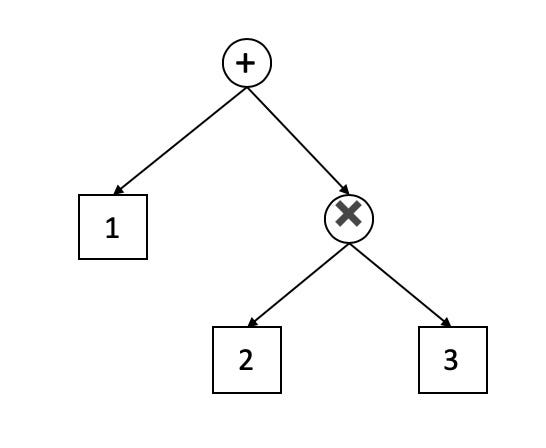

However, this is still not something the calculator can evaluate. For that the input needs to be converted into a full abstract syntax tree (AST)3

An AST is a way to represent a mathematical expression as a combination of Nodes in a tree. Nodes are simply singular values on the tree, with connections to other nodes. In fact, you can use an AST to represent lots of things, with a calculator being one use of them. In the picture you see the representation of “1+2*3” as an AST. Technically there are many ways to represent an equation as an AST. A common representation is to use the binary operators as “connector” nodes, and connect the independent value node (IVN) to using the binary operators. In this context, an IVN is any node that dosent need any other nodes to figure out its value. So like 5, or Sin(x), etc. However a connector node, like “+” or “*” depends on the nodes around it. “+” itself means nothing.

It is relatively simple to convert the partially converted tokens into an AST, because they already come in a convenient order. All we have to do is iterate over the tokens, and apply the following conditions:

- if the token is a “(“: Increase the priority of following tokens

- if the token is a “)”: Decrease the priority of following tokens

- if the token is an independent value node (IVN): Mark it for later

- if the token is a binary operator (“+”, “*”, etc): Since step 2 ensured equation validity, we know that there will be some sort of IVN before hand. Create a binary connector node and set the left child to the beforehand IVN. For now we leave the right child open. If there was a previous binary connector node, this new node becomes that previous node’s right child.

- Once we have reached the last token, set the very last binary connector node to have its right child be the very last IVN. For example 5+1+2, the last 2 becomes the very last right child.

Once we have completed this, we get an AST:

In the examples below, l{level} denotes parenthesis level

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

a+b-c

(+)

(a) (-)

(b)(c)

a+b*c

(+)

(a) (*)

(b)(c)

(a+b)*c

(+ l1)

(a) (*)

(b)(c)

(a+(a+b))*c

(+ 11)

(a) (+ 12)

(a)(*)

(b)(c)

4. Use the AST, and simplify it into an answer

As you saw above with the AST, it is a tree of Nodes. However, the answer you want is probably some sort of number. So we need to somehow simplify the tree into a single number to return. Luckily, we can use a tree traversal, to one by one simply the equation into an answer. We just need to be careful to ensure order of operations.

An very important note is that in the equation 1+1+2*3, 1+1 can be safely evaluated before 2*3. More generally, order of operations only applies to the binary connector node that is nearest to it. So in the case of 1+1+2*3, the the nearest other connector to the first + is another +. So the first + can be safely evaluated. Of course, the second + cannot be evaluated, the * that comes right after must go first

Knowing this tip, a very simple algorithm emerges. Lets walk through it with the equation (1+1)*5+2*3. The AST for this equation looks something like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

(1+1)*5+2*3

(+ l1)

(1)(*)

(1)(+)

(5)(*)

(2)(3)

- Start With the topmost Node (in this case the + binary connector). Lets call it cur

Check: Does cur have another binary connector as a right child? Yes, so:

Check: Does the connector below have higher presedence? No, there are parenthesis around the +, so it can go first.

Action: evaluate 1+1 First. Specifically, apply the binary operator (“+”) to the cur.leftChild independent value node (IVN) and to cur.rightChild.leftChild IVN

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

(1+1)*5+2*3 (+ l1) op1 > (1)(*) op2 > (1)(+) (5)(*) (2)(3)

1+1 = 2, So create a new IVN of value 2. This will be the new leftChild of cur’s right child. Kinda confusing right? Now we have sucessfully simplified the first part of the equation: (1+1)*5+2*3 -> 2*5+2*3

1 2 3 4

(*) (2)(+) (5)(*) (2)(3)

Skipping the next repetitive step (would be same as step one), the equation now simplifies to 10+2*3, or:

1 2 3

(+) (10)(*) (2)(3)

- Once again, we have take + connector to be the cur. Additionally, we have a * connector below it. However, this time the order of operations is not on our side. We have to evaluate 2*3 first, before we can add 10. So we run the simplification algorithm on the next node (the * connector), and then evaluate the + connector. So the simplification algorithm would return 6 (2*3) and finally, we can then add 10 and 6 to get the final result of 16.

High level summary.

The algorithm can be explained as follows:

- Start with the top node.

- Check lower node to see if you go first or second

- If first, evaluate your left argument and the lowers left argument, and then “insert your evaluated value” to be the lower nodes argument new left argument

- If second, let the lower node figure out its answer first, then evaluate your left argument, and the new right result that came from lower evaluating itself.

- Repeat till you are left with a single constant value node

- The value inside is the answer

Footnotes

A trie helps you quickly find words using its starting letters. Wikipedia ↩︎

A custom data structure makes spliting up a list into chunks, more convenient. Code ↩︎

An AST (Abstract Syntax Tree) shows how an expression is put together—where each operation is a piece, and they all connect like branches on a tree to show how the result is built step by step. Wikipedia ↩︎